Clown Poems

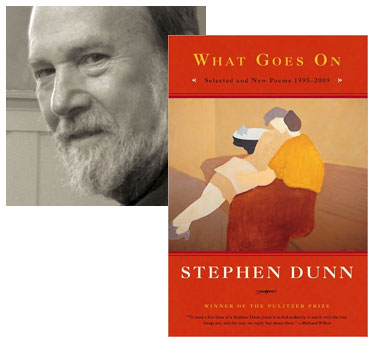

Went to a reading by Stephen Dunn at the Kelly Writers House for class last night. He's written some amazing poems--one about a man seeing a clown waving to him from the distant treeline, and argument he had with his ex-wife about crows traveling in threes, another about being at a party and going upstairs to hang out with the dogs instead, how at a certain time of day, he's more likely to start misbehaving (4 PM), how it's just luck that he's not considered a criminal, just luck that the fire he started didn't spread or luck that a little girl didn't dart out in front of him in traffic when he was driving a little drunk, poems about desire and "this stupid body," and how on hot days in New York, everyone wants everyone, and then this line from one of the poems he read about a writing workshop where he thought he had a great idea and he read it and "the room got quiet with tolerance."

That's what I feared might happen for my workshop last night, but it went fine. We work-shopped two of my poems and people really liked the second one, which is the more playful, less emotionally resonant piece. I guess it's funny. That's one of the things I noticed about Dunn's work--that it's funny, clever, interesting. Maybe I need to write a few more poems that are a little more idea-centric. I'm glad that's over with. I feel lucky to have gone first, so that now I can relax and focus on the revisions and the other poems we have to write each week.

Here is Stephen Dunn's clown poem from the August 24, 2009 issue of The New Yorker

"If a Clown"

That's what I feared might happen for my workshop last night, but it went fine. We work-shopped two of my poems and people really liked the second one, which is the more playful, less emotionally resonant piece. I guess it's funny. That's one of the things I noticed about Dunn's work--that it's funny, clever, interesting. Maybe I need to write a few more poems that are a little more idea-centric. I'm glad that's over with. I feel lucky to have gone first, so that now I can relax and focus on the revisions and the other poems we have to write each week.

Here is Stephen Dunn's clown poem from the August 24, 2009 issue of The New Yorker

"If a Clown"

If a clown came out of the woods,

a standard-looking clown with oversized

polka-dot clothes, floppy shoes,

a red, bulbous nose, and you saw him

on the edge of your property,

there’d be nothing funny about that,

would there? A bear might be preferable,

especially if black and berry-driven.

And if this clown began waving his hands

with those big white gloves

that clowns wear, and you realized

he wanted your attention, had something

apparently urgent to tell you,

would you pivot and run from him,

or stay put, as my friend did, who seemed

to understand here was a clown

who didn’t know where he was,

a clown without a context?

What could be sadder, my friend thought,

than a clown in need of a context?

If then the clown said to you

that he was on his way to a kid’s

birthday party, his car had broken down,

and he needed a ride, would you give

him one? Or would the connection

between the comic and the appalling,

as it pertained to clowns, be suddenly so clear

that you’d be paralyzed by it?

And if you were the clown, and my friend

hesitated, as he did, would you make

a sad face, and with an enormous finger

wipe away an imaginary tear? How far

would you trust your art? I can tell you

it worked. Most of the guests had gone

when my friend and the clown drove up,

and the family was angry. But the clown

twisted a balloon into the shape of a bird

and gave it to the kid, who smiled,

let it rise to the ceiling. If you were the kid,

the birthday boy, what from then on

would be your relationship with disappointment?

With joy? Whom would you blame or extoll?

a standard-looking clown with oversized

polka-dot clothes, floppy shoes,

a red, bulbous nose, and you saw him

on the edge of your property,

there’d be nothing funny about that,

would there? A bear might be preferable,

especially if black and berry-driven.

And if this clown began waving his hands

with those big white gloves

that clowns wear, and you realized

he wanted your attention, had something

apparently urgent to tell you,

would you pivot and run from him,

or stay put, as my friend did, who seemed

to understand here was a clown

who didn’t know where he was,

a clown without a context?

What could be sadder, my friend thought,

than a clown in need of a context?

If then the clown said to you

that he was on his way to a kid’s

birthday party, his car had broken down,

and he needed a ride, would you give

him one? Or would the connection

between the comic and the appalling,

as it pertained to clowns, be suddenly so clear

that you’d be paralyzed by it?

And if you were the clown, and my friend

hesitated, as he did, would you make

a sad face, and with an enormous finger

wipe away an imaginary tear? How far

would you trust your art? I can tell you

it worked. Most of the guests had gone

when my friend and the clown drove up,

and the family was angry. But the clown

twisted a balloon into the shape of a bird

and gave it to the kid, who smiled,

let it rise to the ceiling. If you were the kid,

the birthday boy, what from then on

would be your relationship with disappointment?

With joy? Whom would you blame or extoll?

Comments